Tests Don’t Ask Questions – Good or Otherwise

Take a look at this math sample from a standardized assessment. This is commonly called a test question.

However, where’s the question?

None of the statements in this math sample are written in the interrogative form with a question mark at the end. In fact, every sentence is written in the imperative form, telling students what they need to do – or demonstrate.

Now you might call this a test question because … well, it’s on a test and that’s what tests do – ask questions to assess knowledge and thinking.

However, this is not a question.

It’s actually an item. That’s the technical term. It’s a specific task students are directed to perform in order to meet a particular educational objective. In this case, the students are expected to do or demonstrate the following:

- Use the Add Point Tool to plot each point on the coordinate plane.

- Plot the point (3, 2).

- Plot the point (6, 4).

- Plot the point (8, 1).

If they do this correctly and as directed, then they will have met the 5th-grade math standard this item and task addresses. According to the sample assessment, this particular item addresses CCSS.5.GA.2, which states students will “represent real-world and mathematical problems by graphing points in the first quadrant of the coordinate plane, and interpret coordinate values of points in the context of the situation”.

However, which objective of the standard does this particular problem address? Also, does this item even address the objective? What specifically is the problem presented here? Where’s the real world connection?

Also, look at the cognitive action of the second objective of the standard – interpret, which requires students to explain the meaning of. However, none of the action verbs in this item – useor plot – are synonymous with interpret. Those actions are more synonymous with apply, which is one category under analyze according to Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy.

So how can this assessment accurately claim that this particular item and task addresses that particular 5th-grade math standard since none of the correlating actions address the performance objective of the standard?

More concerning, why is this called a “question” when there are no questions being asked?

Now take a look at this sample item from a practice assessment.

Yes, it does include a question. There is an interrogative statement. However, look at how that question is phrased. How clearly is written? Do you understand what exactly it’s asking? Would a 5th grader understand what exactly it’s asking them to do? What does the word possible infer or suggest? Could there be more than one answer? What would happen if they put down more than more than one number?

Suppose the student addresses the item correctly. Can they explain why the number they chose refutes Lisa’s claim? Could there also be more than one answer? Does 100 have to be multiplied a whole number or could 100 be multiplied by any kind of number such as a decimal?

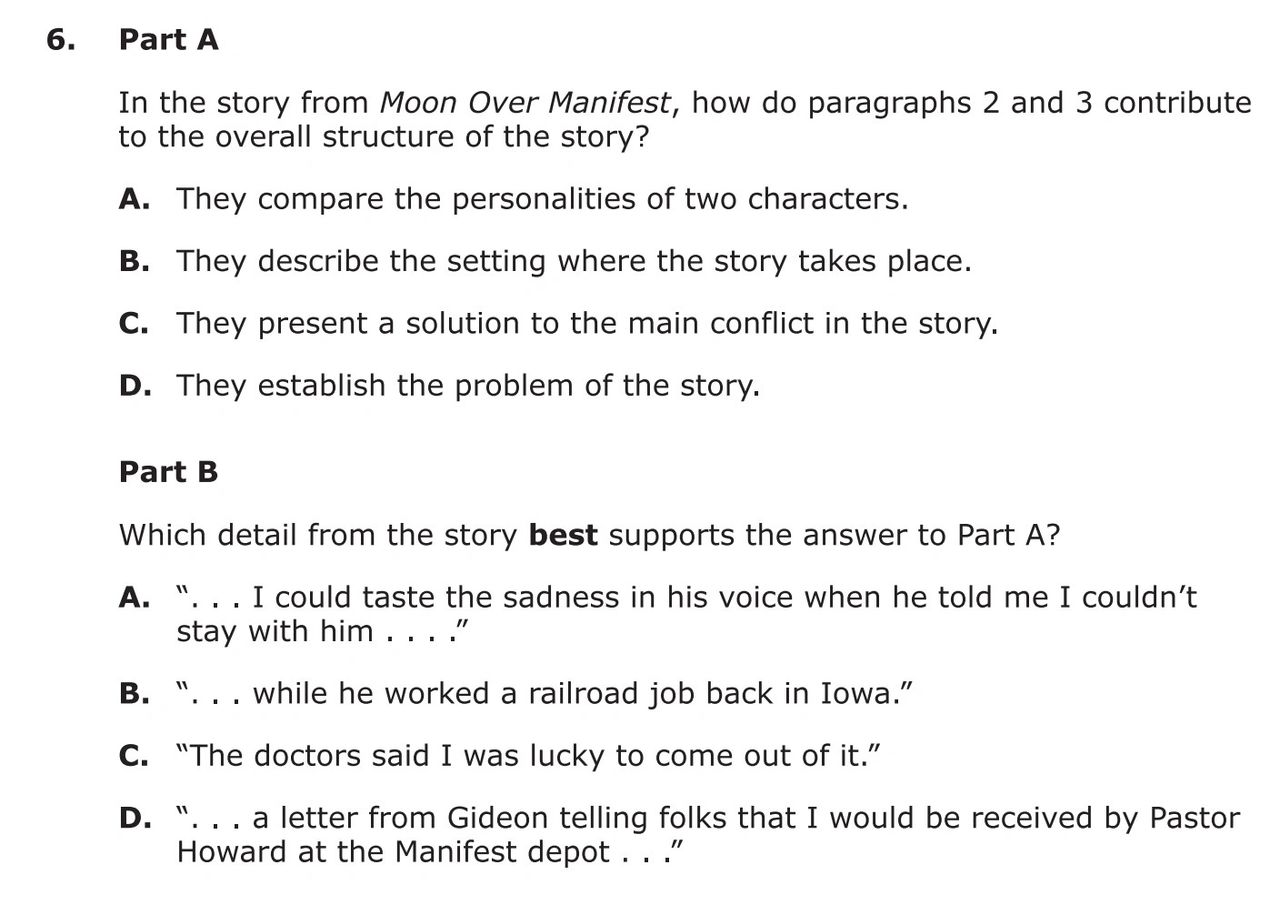

Now take a look at this sample from a practice assessment in English language arts.

Again, these are questions. In fact, these questions more accurately address the objective of the standards they address because they have students apply a literary skill and also support their response. However, can the student elaborate on how paragraphs 2 and 3 contribute to the overall structure of the story or explain which the detail they chose in Part B best supports the answer to Part A? What if the student chooses the incorrect response in Parts A and B – or chooses the correct response for one but not the other? Does that mean they do not understand how to “explain how a series of chapters, scenes, or stanzas fits together to provide the overall structure of a particular story, drama, or poem” (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.5.5) or could it be they did not understand or could not relate to the text they were reading?

How about this item from an ELA practice assessment?

This activity would also be considered a DOK-4 because it challenges students to ” analyze and synthesize information from multiple sources” and “examine and explain alternative perspectives across a variety of sources” (Webb, 2002). It directs students to refer to the two different passages they read and “answer question 7”. However, where is that question they need to answer? Number 7 of the assessment just directs students to “[w]rite an essay describing how each narrator’s point of view influences how these events are described”. It also emphasizes that the students “[b]e sure to use details from both stories”. Directions are given and expectations are set, but no questions are asked!

This is not a matter of semantics. Why? Because these are NOT questions! More specifically, they are not good questions that challenge and engage students in thinking deeply and expressing and sharing the depth and extent of their learning. More concerning, these activities, items, and tasks do not truly measure the depth and extent of students’ learning. All they indicate is whether the student can address THAT particular problem, accomplish THAT particular task, or complete THAT activity correctly and as directed in THAT particular moment or on THAT particular day.

So how can we develop good questions that will not only assess the depth and extent of student learning but also challenge students to demonstrate and communicate their learning?

In my ASCD book Now That’s a Good Question! How to Promote Cognitive Rigor Through Classroom Questioning, I share a process educators can use to turn the imperative sentences of academic standards and educational objectives into interrogative sentences that can be used as good questions to set the instructional focus and serve as assessments for deeper student learning experiences. I call this process “Show and Tell”, and it involves the following:

- Identify what is the performance objective. This is the imperative statement that starts with a verb or a verb phrase. We also call them directions. In academic standards, determine whether it has one or more performance objectives or is phrased as a compound sentence. For example, the math standard, “Understand the concept of a ratio and use ratio language to describe a ratio relationship between two quantities,” has two performance objectives written in a compound sentence.

- Place “Show and Tell” in front of the standard. It won’t sound grammatically correct initially – but that’s good! It will help us turn it into a question. If you notice in the Show and Tell graphic, the phrase is very light and almost invisible. That’s because it will disappear once we create our good question.

- Choose a question stem from the Bloom’s Questioning Inverted Pyramid (BQIP) or the Cognitive Rigor Question (CRQ) Framework. These graphics are featured in my book ASCD Now That’s a Good Question! How to Promote Cognitive Rigor Through Classroom Questioning. I included an updated version of the BQIP previously in this blog. My updated CRQ Framework is also featured next to the first step in this section.

- Follow the question stem with a linking or helping verb. Click here if you need to familiarize (or refamiliarize) yourself with what these verbs are.

- Identify the subject matter that will be taught. This is generally the main focus or topic of the standard. In the standard, “Understand the concept of a ratio and use ratio language to describe a ratio relationship between two quantities,” the subject matter is ratio, ratio language, and ratio relationship.

- Write the cognitive verb in the past tense with the verb be in front of it. Most of the communication we express and share should be in the active voice. However, more often than not, you will find your good question will be in the passive voice. For example, the performance objective, “Understand the concept of a ratio,” will be rephrased as How can the concept of ratio be understood?

- State the purpose. This is the context in which students will demonstrate and communicate their learning. The purpose can be the scenario, setting, or situation in which students transfer and use their learning. It can also be the evidence or proof students will produce or provide that they learned the subject matter. Some standards and objectives include this. Most do not. The objectives Understand the concept of ratio and Use rate language do not include a purpose. However, the purpose can be the rest of the objective completing the compound sentence. For example, we can as How and why can the concept of a ratio be understood by describing a ratio relationship between two quantities? or How can ratio language be used to describe a ratio relationship between two quantities? The first question is reflective and the second question is analytical. The purpose of the objective can also be turned into an analytical question (How can a ratio relationship between two quantities?) or affective (How could you describe a ratio relationship between two quantities?).

Try using the “Show and Tell” method to help you rephrase the imperative sentence of academic standards, educational objectives, and instructional directions into interrogative sentences that will become good questions that will not only truly assess but also set the clear expectations for how students will demonstrate and communicate their learning. The questions you will create will be much better than the items provided on assessments.

Erik M. Francis, M.Ed., M.S. is an author, educator, and speaker who specializes in teaching and learning that promotes cognitive rigor and college and career readiness. . He is also the author of Now THAT’S a Good Question! How to Promote Cognitive Rigor Through Classroom Questioning published by ASCD. He is also the owner of Maverik Education LLC, providing academic professional development and consultation to K-12 schools, colleges, and universities on developing learning environments and delivering educational experiences that challenge students to demonstrate higher order thinking and communicate depth of knowledge.